The unique selling point of Raft is that it’s easy to understand – at least, far more so than it’s scary older cousin Paxos. Although I’ve read a Medium article or two about it, and played around with the visualizer, I figure a good way to really get it is to implement it directly from the paper. But first we need to actually read the paper. Here follow my notes from doing exactly that.

I’ll probably have a peek or two at TiKV’s raft-rs implementation if I get a little stuck, or if I’m looking for some inspiration, but I’ll do my darnedest to do as much of it as possible directly from the paper. Having skimmed it already, it seems more than doable. I guess there’s no real point in designing an understandable consensus algorithm if nobody can understand the paper itself, but kudos to the authors anyway for their approachable writing style.

(Too many academics fall into the trap of ‘opaque = clever’; myself included, when I dabbled in academic writing back in varsity. Oops.)

To squash any potential claims of plagiarism, I want to make it abundantly clear that none of what I’m going to be describing below will be new, and I do not claim any of the ideas below as my own. That honour goes to Diego Ongaro and John Ousterhout of Stanford University, Raft’s illustrious authors.

So what is Raft anyway?

Raft is an algorithm to implement consensus between a collection of servers, called a “cluster”. The goal of a consensus algorithm boils down to replicating the same thing reliably across multiple servers, so that if some subset of the servers goes offline, the most recent changes to that thing are saved, and operation can continue as normal. In the case of Raft, that thing being replicated is a state machine, the idea being that all the servers in the cluster will eventually contain the exact same state machine.

More concretely, Raft replicates a log of entries, and all constituent servers will eventually contain an identical set of these log entries. These log entries describe state transitions, or the operations that are applied to the state machine. Apply those entries to a blank state machine in order, and you end up at the same ‘final’ state machine (state machines are by definition deterministic); and if all the servers have the same entries, all these final state machines will be the same! Strictly speaking, though, the log entries don’t have to represent a state machine. There is nothing preventing you from using Raft to replicate literal logs – as in, strings of text – across multiple servers, if you desperately wanted to.

Leader election

Raft uses a strong leader model: a Raft chooses from amongst its members one to be a leader. The leader handles all the client requests, and is responsible for ensuring that log entries are safely and durably replicated to the other nodes in the cluster. The leader’s word is law: if a node disagrees with the leader, they will be made to delete any conflicting log entries until agreement is reached.

Raft divides time into sections known as terms. A term starts with a leader election, and lasts until that leader is somehow ousted – in other words, until the leader is for some reason or another not contacting some subset of the other nodes in the cluster. Like presidential terms, Raft terms are defined by a single leader; unlike presidential terms, Raft terms are not limited by actual wall time (i.e. no 4 year term limit). Terms are associated with a term number, an integer used to identify a term between servers, which increases monotonically as elections happen. This allows terms to function as a rudimentary clock: if one term number is less than another, the lower term number is stale, and the command can probably be rejected!

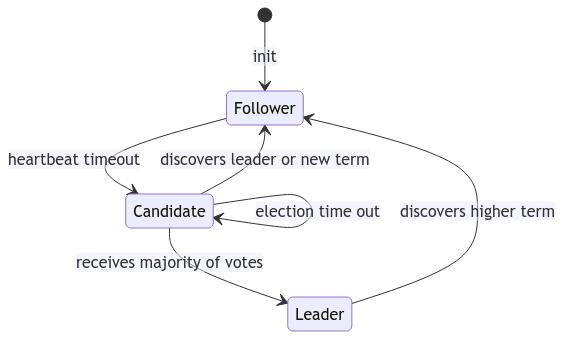

Servers in Raft have three potential states: follower, candidate and leader. Followers are happy to remain followers, and as long as they have evidence that their leader is alive and well, they will stay in this state, committing the log entries that they are receiving from their leader. This evidence of leader liveliness comes in the form of a regular heartbeat: the leader will constantly ping its followers to prove that it is still around.

If too much time passes between received heartbeats, a follower will have no choice but to assume that their leader is dead, and will transition to the candidate state, in an attempt to become the cluster’s new leader. It does so by incrementing its own current term, and then requesting votes from all of the other servers in the cluster. It also casts a vote for itself>.

A candidate transitions to a new state under one of the following conditions:

- the candidate receives votes from the majority of servers in the cluster. It then transitions to leader for this term, and begins sending heartbeats to all of the servers in the cluster to

assert dominanceestablish its new role and prevent new elections from being triggered. - the candidate receives a heartbeat or append-entries command from another server claiming to be leader; the candidate will only respect the authority of this server if it has a term number that is greater than or equal to the term number of the candidate. If this is the case, the candidate happily transition back to follower, and follows the orders it just received from the leader; otherwise, the server remains in the candidate state.

- the candidate does not receive a majority of votes in the cluster, but nor does any other server. In this case, the candidate times out, and starts a new election, incrementing the term once again, and staying in the candidate state.

Note that each server in a cluster will only ever cast a vote for a single server per election, and it will always vote for the first server that requests a vote from it.

You may have spotted an issue here: if the leader goes down, and all of the servers transition to candidate at the same time, and all vote for themselves, nobody will be elected! And then the election will time out, and each candidate will re-request votes, and vote for themselves, and nobody will be elected, and the election will timeout! Ad infinitum!

Thankfully, the Raft designers were clever enough to foresee this: a random election timeout is used per server per term. So the server with the lowest timeout will see the missing heartbeat first, transition to candidate, and likely get the majority of votes from its compatriots; and even if two or more servers happen to be candidates at the same time, and none get a majority of votes, one of these candidates will reach their election timeout before the others, and will trigger an election in a new term first. While there is a chance that we hit the ad infinitum re-election cycle, the probability of this becomes vanishingly small as the number of elections increases, unless you’re using an absolutely awful random number generator.

This is represented by the following state machine:

Neat! Very few states and transitions to represent a robust and digestible leader election system!

A good place to stop

Leader election is just one part of a larger story, albeit a very important one. At this stage, we are able to elect a server to act as the leader of our cluster, but we can’t really do much with the cluster yet. Keep an eye out for part 2, where we will dive into how Raft replicates logs from the leader node to the followers, in a safe, reliable, fault-tolerant, understandable manner.

[There is another element to leader election – specifically, under what conditions a server will cast their vote for another server. It is quite entangled with log replication, though, so we’ll save that for the next part.]