Following on from part 1, in which we learned about Raft’s leader election mechanism, we continue our journey into the Raft paper. In this installment, we’re learning about Raft’s approach to log replication.

The problem with log replication

In an ideal situation, absent of faults, dropped packets and server crashes, log replication is incredibly simple: a leader receives a request from a client; they apply the request to their own state machine; they instruct each of their followers to apply it to the follower’s own state machine. Easy as that.

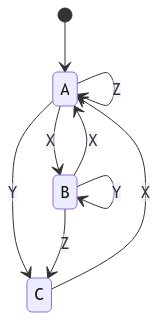

Unfortunately, faults do happen, and if we did follow this naive approach, we’d end up with followers with state machines diverging from each other, and from the leader’s own. Imagine a state machine with states A, B and C with operations X, Y and Z as follows:

If this machine is subject to the transitions X, X, Y, they should end up in state C (A --[X]--> B --[X]--> A --[Y]--> C); but if one of the X operations is dropped, for example because a follower crashed during a log replication call, their state machine will end up in state B instead. This state machine divergence is unacceptable: the goal of a replicated state machine is to get every participant to agree on state machine state, which we’ve clearly failed here.

Thankfully, Raft has come up with a simple way to remedy this. The leader keeps track of which logs it has sent to each of its followers to replicate; until a follower indicates indicates that a log has been successfully replicated, the leader will keep trying to replicate a log to it. There’s a chance now that a log will be applied twice to a follower, so to be extra-safe, we’ll give the log an integer index; followers can use these as identifiers, and prevent themselves from applying the same log twice!

With this in place, we won’t be losing state machine operations anymore! If a server ever crashes, or packets are dropped, the follower will simply receive the logs again at a later point, when the network stabilizes or when the server reboots! Leader and follower agree on state C! Hooray!

Unfortunately, this is still insufficient: we still haven’t dealt with the possibility of leader crashes. If a leader crashes mid-way through replicating some log to its followers, there is a strong chance that, after an election is triggered, the next leader’s state machine is different from the crashed former leader; and even if it happens to be the same, there will be followers in the cluster that had not successfully replicated the log that the former leader was busy sending out. The new leader’s state has diverged from the state of some of his followers, and any transient state that the old leader had about which logs each follower had successfully replicated is now lost! We need a way to resolve state on leader election, and to prevent candidates who do not have the ‘latest’ version of the state machine from being elected leader.

Raft’s log replication solution

Thankfully, the Raft authors have come up with a robust, simple solution to this problem. The core idea is to add an entry to the log and apply the entry to the state machine in distinct steps. Adding an entry to the log is cheap and easy; provided that certain simple invariants are not violated, we can add entries to our logs quite liberally; and since we’re not modifying the state machine yet, we don’t have to worry about state divergence.

The leader is then responsible for determining when it is safe to actually apply an entry to the state machine; we call such an entry committed. Raft’s lovely simplicity kicks in here again: an entry can be committed as soon as it has been successfully replicated to a majority of the cluster.

This allows us to add another condition to leader election: a member will only vote for a candidate if the candidate either has a higher current term than the member, or their current terms are equal and the candidate’s latest log index is greater than or equal to the member’s latest log entry. This mechanism prevents a candidate without the latest committed entry from being elected: a log entry is considered committed once it is broadcast to a majority of the cluster, and a candidate requires a majority of the cluster to vote for it; thus, at least one of the members in the voting set must also have the latest committed log, and they would not vote for the candidate if the candidate did not also have the latest committed entry.

Appending entries

Finally we can discuss what happens when a user wants to make a request against a Raft cluster.

From the leader’s perspective:

- The leader receives a request from the client.

- The leader adds the entry to its own log, thereby incrementing its own log index.

- The leader sends an AppendEntries call to every follower in parallel, instructing the follower to add the new log to its own state machine

- If the leader knows that the follower has fallen behind, it will earlier logs on this RPC as well, to help it catch up

- If a follower rejects the RPC, and indicates a term higher than the leaders’ own, the leader will transition to follower, and respond to the client as if it is a leader.

- If a follower rejects the RPC because the entry is not logically next, send the log entry immediately preceding the new one as well

- Once a majority of followers have added the log entry to their own logs, the leader treats it as committed, and adds it to its own state machine

- In future AppendEntries calls, the leader will indicate that the new entry is committed, so followers can apply the entry to their own state machines.

- The leader responds to the client, indicating success.

From a follower’s perspective:

- The follower receives an AppendEntries call.

- If the requester’s term is less than the follower’s known currentTerm, the AppendEntries rpc is rejected, and the follower indicates what their currentTerm is set to.

- The leader will use this information to become a follower

- If the new entry is not logically the next index, reject the new entry

- This will cause the leader to send older entries so the follower can catch up

- If the new entry is in conflict with the followers existing log entry (i.e. an entry with the same index, but different terms) delete the conflicting existing entry, and all entries following it

- Append the entry to the log

- For every entry yet to be committed that has a logIndex less than or equal to the commitIndex in the AppendEntries call, apply that log to the state machine

- Respond to the leader, indicating success.

That’s it! Log replication in just a few bullet points.

Wrapping up

So there we have it: replicated state machines that people can actually understand. In fact, all of this is summarized even more neatly in the raft paper, in Figure 2; Figure 2 is, in fact, probably sufficient to completely implement the Raft algorithm!

The Raft authors have, in my opinion, crafted a brilliant, easily-digestible algorith, that should be (🤞) very straightforward to implement. I’m going to be giving it a try now. I’ll update the blog if I manage!